The Price of Gold: Canada’s Ongoing First Nations Water Crisis

Throughout January, 2026.3 min read

Many First Nations communities around Canada—a country with a significant percentage of the world’s freshwater reserves, romanticised as an endless source—see a significant irony every day. While urban communities outside of First Nations reserves have all the clean water they need, there are still 31 long term drinking water advisories spanning through 29 reserves, many of them existing for at least a quarter of a century. This isn’t simply a small failure with Canada’s system, but a violation of human rights in a country where this should logically never happen.

Disclaimer

I am not of Indigenous descent and do not speak on behalf of any Indigenous community or individual. This article is written from a research perspective, and I have done my best to write with the aim of raising awareness and sharing information about the ongoing First Nations water crisis in Canada. For authentic voices and perspectives, please seek out Indigenous-led organizations and resources such as those in the sources I listed below.

Broken Promises

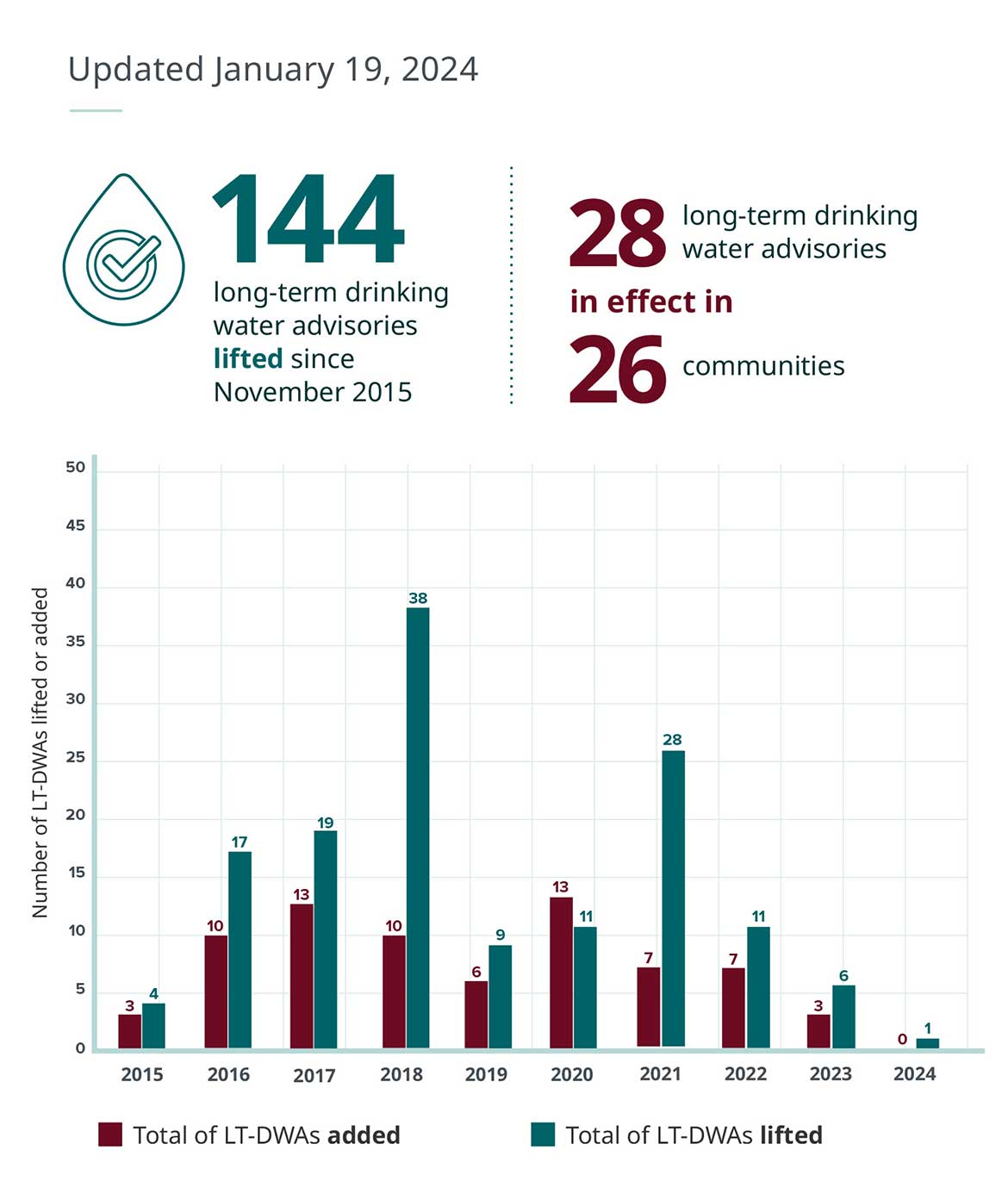

After large promises made in 2016 by then-Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau to lift all 186 drinking water advisories, there are still 31 outstanding—10 years later. It can be seen that through different years the government has made varying amounts of progress, some surpluses but also many deficits.

While this may seem like a small number, The Council of Canadians quotes that, “A single drinking water advisory can mean as many as 5,000 people lack access to safe, clean drinking water.” (Council of Canadians). This means that up to 155,000 Indigenous people lack access to a basic human right. To be able to drink or at all use their water, they must boil it for at least a minute, further waiting for it to cool. (Indigenous Foundation). This is not only time consuming, but expensive, and just simply not a justifiable reality for many people.

One mother even discusses that she must, “sponge [her son with a skin disease] with bottled water from the jugs, clean him that way”, the only way she can safely take care of him.

Others have to limit showers for both themselves and their children just to limit exposure to dangerous contaminants such as:

- Bacteria: Such as E. coli and coliform.

- Carcinogens: Including Trihalomethanes.

- Heavy Metals: Such as uranium.

The daily reality for these residents is grueling. Simple acts like brushing teeth or bathing a child become high-risk activities.

(Council of Canadians)Gaps in Funding and Training

When looking into the true causes behind these issues in First Nations communities, we can come to the conclusion on two main sources: gaps in funding and training. The Parliamentary Budget Officer identified deficits amounting to $138 million per year just for the maintenance and operation of basic water systems. However, money isn’t the only root of unclean water, there is a critical shortage of certified water professionals within First Nations communities. Only about 45% and 51% of 143 and 160 First Nations communities respectively in Ontario and British Columbia had water systems with a fully trained certified operator. (Bharadwaj et al.)

This isn’t just a gap of will but a lack of support. Canadians have the resources to provide this essential service but rather choose not to supply it, leaving communities who need it the most to be lacking. Furthermore, the already existing certified operators admit issues in their job, being “understaffed, overworked and underpaid”(Baijius and Patrick)

The Legacy of the Water Walker: Josephine Mandamin

Born Feb. 21, 1942, Josephine “Grandmother Water Walker” Mandamin was a prominent award winning Anishinabek figure. She is known best for her actions of raising awareness for water pollution and environmental degradation throughout indigenous reserves and great lakes.

At a conference in the year 2000, a friend of hers had a dream where water would cost the same as gold by the year 2030.(Marshall). Refusing to let this dream become a reality, Mandamin committed herself to sharing her “nibi giikendaaswin” (water knowledge) in order to fight for the future and started a group of “Water Walkers”. (Marshall). From 2003 to 2017, she—with her group—walked over 25,000 kilometers around the Great Lakes to raise awareness about water pollution and Indigenous rights.

Mandamin’s protest was somewhat successful, pressuring the government enough to lift 88 of the water advisories hurting Indigenous communities, though some are still outstanding. Throughout her lifetime, she received many awards including a name “Biidaasige-ba” (the one who comes with the light), a lifetime achievement award (2012), and the Governor General’s Meritorious Service Cross (2018). (Museum of Toronto). Sadly, she passed away in 2019, but her legacy continues to live on and her great-neice—Autumn Peltier—, along with her daughter, following in her footsteps.

Humans Right Violation as part of the United Nations

The United Nations recognizes the access to safe water as a basic human right, and Canada—as a rich nation part of the UN—somehow still lacks this. The dangers of this are even more than just contaminants. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some communities like Neskantaga were forced to evacuate because of lack of effective infection control. (Baijius and Patrick). The "water crisis" is not an invisible problem, it is a visible choice made through underfunding and systemic barriers. As we approach the year 2030—prophesied to have "gold-priced water"—the question remains: Will Canada finally honor its obligations to its original inhabitants, or will the taps stay dry and dirty?

Works Cited

- City of Thunder Bay. “Grandmother Josephine Mandamin.” Www.thunderbay.ca, 29 Oct. 2019, www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-hall/grandmother-josephine-mandamin.aspx. Accessed 15 Jan. 2026.

- Gallant, David Joseph. “Josephine Mandamin | the Canadian Encyclopedia.” Www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca, 2 Oct. 2020, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/josephine-mandamin. Accessed 11 Jan. 2026.

- Government of Canada. “Ending Long-Term Drinking Water Advisories.” Government of Canada, 25 Jan. 2024, www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1506514143353/1533317130660.

- Kehinde, Mercy O, et al. “Weaving Knowledge Systems to Eradicate Drinking Water Crises in First Nations across Canada.” Journal of Water and Health, vol. 23, no. 9, 1 Sept. 2025, pp. 991–1003, iwaponline.com/jwh/article/23/9/991/109379/Weaving-knowledge-systems-to-eradicate-drinking, https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2025.346.

- Klasing, Amanda. “Make It Safe | Canada’s Obligation to End the First Nations Water Crisis.” Human Rights Watch, 7 June 2016, www.hrw.org/report/2016/06/07/make-it-safe/canadas-obligation-end-first-nations-water-crisis.

- Murphy, Heather M, et al. “Insights and Opportunities: Challenges of Canadian First Nations Drinking Water Operators.” International Indigenous Policy Journal, vol. 6, no. 3, 18 June 2015, https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.3.7.

- Museum of Toronto. “Josephine Mandamin - Museum of Toronto.” Museum of Toronto, 2 Apr. 2024, museumoftoronto.com/collection/josephine-mandamin/. Accessed 14 Jan. 2026.

- The Council of Canadians. “Safe Water for First Nations.” The Council of Canadians, 13 Nov. 2019, canadians.org/fn-water/.

- Yenilmez, Sena. “Indigenous Safe Drinking Water Crisis in Canada.” The Indigenous Foundation, 29 May 2025, www.theindigenousfoundation.org/articles/indigenous-safe-drinking-water-crisis-in-canada-overview.